December 2, 2025

“The space and place we inhabit produce us.” – Elspeth Probyn (2003)

When you think of social work, what comes to mind? Helping people. Fighting for justice. Making life better for those who need support. Perhaps so. However, social work does not exist in isolation. It is shaped by history, geography, and power. Probyn’s insight that ‘the space and place we inhabit produce us’ reminds us that identity is not formed in a vacuum. Our sense of self is connected to the spaces we occupy—whether classrooms, workplaces, or communities.

Social work may have been built upon good intentions, but it is a profession that is deeply embedded within socio-political and historical contexts, and this means it was also built upon systems that uphold white supremacy and colonial thinking (BlackDeer & Ocampo, 2022). Even today, social work education and curricula often focus upon Eurocentric theories while ignoring Indigenous and non-Western perspectives (Tusasiirwe, 2024). This does not allow for a critical engagement with the contentious history of social work, alongside its current complicity with oppressive structures (Ioakimidis & Wyllie, 2023).

We must critically examine how space, place and identity intersect and how these intersections reproduce inequality. This means recognising how institutional structures and cultural norms impact upon individuals and communities. Probyn’s concept of ‘space and place’ enables us to begin interrogating how spatial and structural arrangements reproduce racialised inequalities.

In the case of the UK’s No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) condition, NRPF does not merely function as an abstract legal restriction; it is enacted through local authorities, welfare systems, and urban infrastructures, shaping racialised geographies of exclusion that disproportionately impact Black and minoritised communities.

For example, 82% of NRPF cases involve people of colour (Citizens Advice, 2020), with Black and minoritised children often denied free school means due to parental NRPF status (Rosen & Dickson, 2024). Additionally, the gendered dimensions of NRPF are stark, with approximately 85% of applications to lift NRPF restrictions coming from predominantly single mothers from ethnic minority backgrounds (Woolley, 2019). These restrictions, combined with misinformation about those subject to immigration control fuel harmful narratives that undermine social cohesion and human rights.

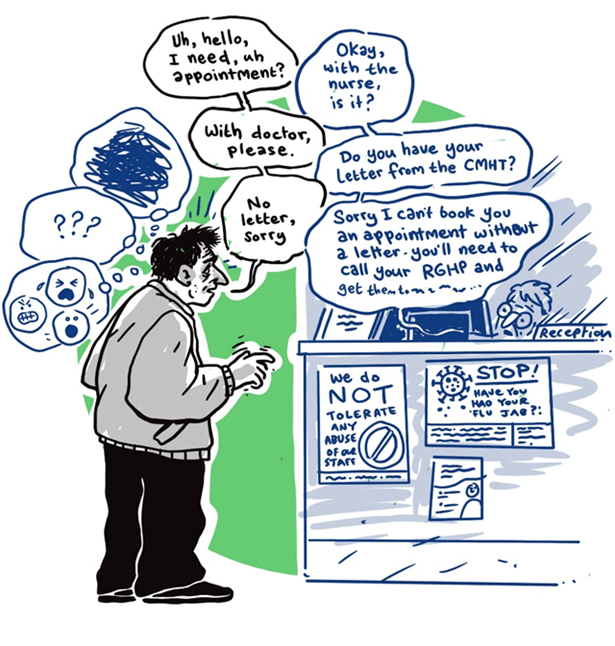

The ‘space and place’ of NRPF creates intersectional harms and racialised geographies of welfare exclusion. Social workers often stand at the frontline of these entranced structural inequalities as the first point of contact with families with NRPF. They are tasked with safeguarding vulnerable individuals while navigating complex legal frameworks and systemic inequalities. Furthermore, they must balance immigration restrictions with duties under human rights and children’s legislation. This often means:

- Advocating for emergency support to safeguard and promote the welfare of children who are in need.

- Navigating bureaucratic systems that prioritize immigration control over welfare.

- Addressing trauma, isolation, and exploitation risks among those subject to immigration control.

Navigating this challenging context requires knowledge and skills that can interrogate how spatial and structural arrangements reproduce racialised and intersectional inequalities. However, research shows that newly qualified social workers often feel underprepared to address racism in practice, revealing that white privilege and systemic racism remain under-discussed, leaving many unable to challenge oppressive structures (Tedam & Cane, 2022).

Understanding the impact of NRPF means recognising how immigration control intersects with histories of colonialism and racial capitalism. Minh-ha (2010) argues that critical engagement with power and knowledge is not oppositional for its own sake but essential for survival and justice. Families who are subject to immigration control is not accidental; it is produced by structural arrangements that privilege certain lives over others. This means that addressing NRPF is not only a legal and ethical challenge—it is also a question of epistemic justice and decolonising practice (Anka, 2024).

Decolonising social work cannot simply be a buzzword. Acknowledging that the ’space and place’ of social work in the UK has historically evolved within Eurocentric frameworks that marginalise non-Western knowledge systems and perpetuate structural inequalities (Garrett, 2024) is only a first step. Decolonisation in social work must involve the dismantling of colonial legacies embedded in curricula, practice, and policy. For example:

- Challenging colonial legacies in education, policy and practice.

- Recognising intersectionality—how race, gender, class, and immigration status intersect to shape vulnerability.

- Challenging White dominance in professional norms.

- Institutional accountability for racism.

To respond effectively to NRPF-related harms, engaging with Critical Race Theory (CRT), Black Feminism and Intersectionality provide foundational insights into the systemic nature of racism. These perspectives challenge colour-blind approaches and underscore the necessity of decolonising social work curricula.

For example, CRT provides an analytic lens to examine how racism is embedded within society, including social work (Pajak, 2024). It challenges colour-evasive practices and calls for counter-storytelling that amplify the voices of those most affected. Applying CRT in NRPF contexts means recognising that immigration control is not race-neutral; it disproportionately impacts racialised individuals and communities and perpetuates structural inequality. Black Feminist thought compliments this approach by foregrounding the lived experiences of Black women, highlighting the interplay of race, gender, and power (Hill Collins, 1990).

In particular, intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) offers a transformative lens for social work by highlighting how race, gender, class, immigration status, and other axes of identity intersect to shape oppression (Bernard, 2021; Nayak, 2022). For NRPF cases, intersectionality reveals how immigration restrictions compound racial discrimination, gendered violence, and poverty—issues often treated in isolation within mainstream practice. Lorde’s (1984) assertion that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ signals the limitations of reformist strategies within oppressive systems. Anti-racist practice requires rejecting dominant paradigms and embracing knowledge systems rooted in marginalised experiences.

For social work, this necessitates pedagogical approaches that integrate activism, critical reflection, and praxis. Moreover, an intersectional lens critiques the profession’s historical and current complicity in racial oppression and calls for a validation of lived experience as knowledge. Intersectional paradigms not only illuminate structural inequalities but also inform strategies for resistance and transformation.

Our research extends these concepts by interrogating whose knowledge counts and prioritises the voices of those with NRPF, who are navigating intersecting vulnerabilities, including precarious legal status, economic marginalization, and racial discrimination. By involving those with lived experience at every stage of our research, we are committed to ensuring that our research is collaborative. Our stakeholder group and Lived Experience Advisory Panel include women with lived experience of NRPF alongside practitioners from refugee and migrant support organisations.

Alongside our quantitative survey, qualitative interviews will be essential to capture the emotional and practical lived realities behind statistical patterns. NRPF isn’t just a policy – it’s a lived reality shaped by race, gender, class, and immigration status and listening deeply to lived experience is a form of epistemic justice, valuing knowledge rooted in real life, not just theory. Ultimately, we need stories, voices, and perspectives that show the human cost of NRPF and the resilience of those navigating it.

References

Anka, A. (2024). Using the concept of epistemic injustice and cultural humility for understanding why and how social work curricular might be decolonized. Social Work Education, 43(9), 2880-2896.

Bernard, C. (2021). Intersectionality for social workers: A practical introduction to theory and practice. Routledge.

BlackDeer, A. A., & Ocampo, M. G. (2022). # SocialWorkSoWhite: A critical perspective on settler colonialism, white supremacy, and social justice in social work. Advances in Social Work, 22(2), 720-740.

Citizens Advice. (2020) Citizens Advice reveals nearly 1.4m have no access to welfare safety net assessed from https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/citizens-advice-reveals-nearly-14m-have-no-access-to-welfare-safety-net/

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought in the matrix of domination. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment, 138(1990), 221-238.

Collins, P. H. (2022). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine (pp. 139–168). In University of Chicago legal forum (Vol. 1).

Garrett, P. M. (2024). What are we talking about when we are talking about ‘decolonising’ social work? The British Journal of Social Work, 54(5), 2027-2044.

Ioakimidis, V., & Wyllie, A. (2023). Learning from the past to shape the future: uncovering social work’s histories of complicity and resistance. In Social Work’s Histories of Complicity and Resistance (pp. 3-28). Policy Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider. Essay’s and Speeches by Audre Lorde. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press.

Minh-Ha, T. T. (2010). Elsewhere, within here: Immigration, refugeeism and the boundary event. Routledge.

Nayak, S. (2022). An intersectional model of reflection: is social work fit for purpose in an intersectionally racist world?. Critical and Radical Social Work, 10(2), 319-334.

Pajak, A. (2024). Critical Race Theory: Origins, Principles, Applications, and Evidence. Advances in Social Work, 24(3), 580-593.

Probyn, E. (2003). The spatial imperative of subjectivity. Handbook of cultural geography, 290-299.

Rosen, R., & Dickson, E. (2024). The exceptions to child exceptionalism: Racialised migrant ‘deservingness’ and the UK’s free school meal debates. Critical Social Policy, 44(2), 201-221.

Tedam, P., & Cane, T. (2022). “We started talking about race and racism after George Floyd”: insights from research into practitioner preparedness for anti-racist social work practice in England. Critical and radical social work, 10(2), 260-279.

Tusasiirwe, S. (2024). Disrupting colonisation in the social work classroom: Using the Obuntu/Ubuntu framework to decolonise the curriculum. Social Work Education, 43(8), 2170-2184.

Woolley, A. (2019). Access denied: The cost of the ‘no recourse to public funds’ policy. London: Unity Project.